Ban the Box Master Post

By Angela Li

Doleac testimony: Empirical evidence on the effects of Ban the Box policies

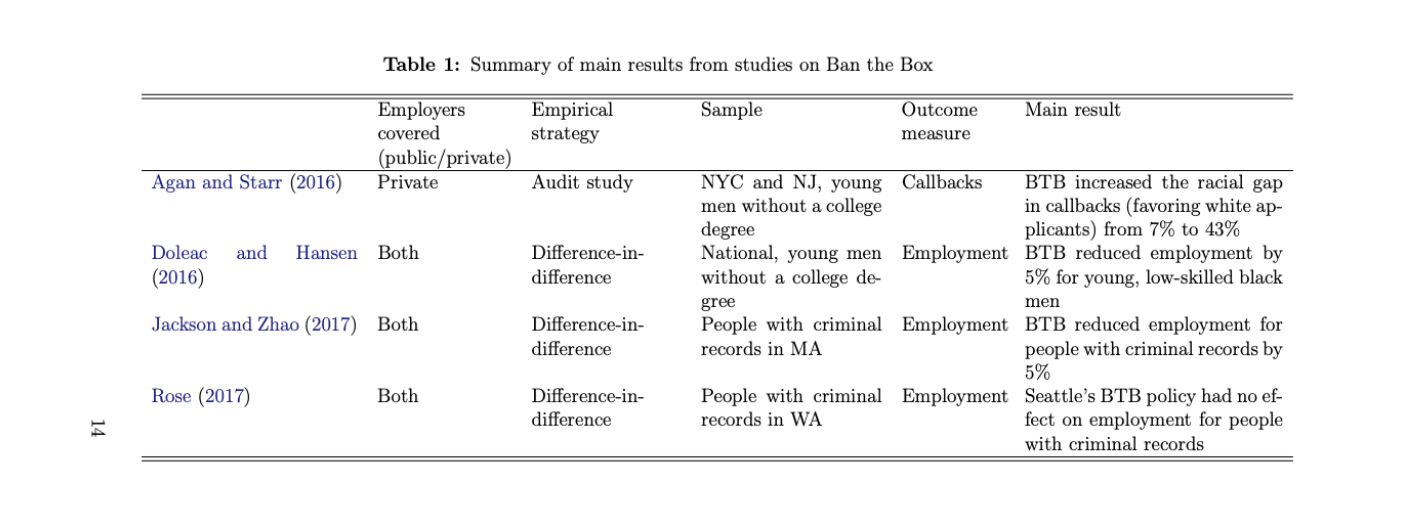

On December 13, 2017, Jennifer Doleac testified before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform on the effectiveness and consequences of BTB policies. Doleac synthesized many studies that have been conducted on the topic, including Agan and Starr 2016, Doleac and Hansen 2016, Rose 2017, and Jackson and Zhao 2017. The four main points are summarized as such:

Delaying information about applicants’ criminal records (CR) leads employers to statistically discriminate against groups that are more likely to have a recent conviction, reducing employment for young, low-skilled black men.

BTB especially hurts employment for young, low-skilled black men without CR. When those men lose the opportunity to signal to employers that they have a clean record, employers assume they do have a CR and do not interview them.

Not only does BTB reduce employment black men without CR, it also does not increase employment for people with CR, and in fact might even reduce employment.

More effective policies should directly address employers’ concerns about hiring people with CR, such as investing in rehabilitation, providing more information to employers about applicants’ job-readiness and criminal history, and clarifying employers’ legal responsibilities.

Table 1 summarizes the main results from the studies references by Doleac. Agan and Starr and Doleac and Hansen are also included in this annotated bibliography.

Doleac states that successful policies for increasing employment for people with CR will need to directly address the concerns that employers hold about hiring people with CR. Such policies may focus on improving the work-readiness of people with CR (investments in education, training, behavioral health treatments), providing more information to employers about the work-readiness of applicants with CR (court-issued certificates of qualification for employment), and clarifying employers’ legal responsibilities in hiring people with CR (shift the ‘risk’ of hiring someone with CR from the employer to someone else, such as the court or judge that issued the certificate of qualification). In general, many studies have found that when information about CR is more readily available, employers do not have to use race, gender, age, or educational level as a proxy for gauging CR and work-readiness. Thus, policies like BTB which take away information from employers are likely to hurt people with CR in terms of employment.

Agan and Starr 2016: BTB, CR, and Statistical Discrimination: A Field Experiment

In this field experiment, Agan and Starr sent 15,220 fictitious online job applications to private, for-profit employers in New York City and New Jersey, both before and after the adoption of BTB policies (which took effect on March 1, 2015 for NJ and October 27, 2015 for NYC). The researchers focused on chain businesses and jobs suitable for candidates with limited work experience, no higher education, and no specialized skills. They also signaled each applicant’s race by assigning “racially distinctive” first and last names, rather than directly indicating race on the application. They sent the applications in pairs matched on race (black or white), and randomly varied whether the applicants had a felony conviction, a GED, or a one-year gap in employment, all characteristics that signal criminal history to employers. Key findings are summarized as follows:

Applicants without a CR are 63% more likely to be called back than an applicant with a CR, confirming that having a CR is a major barrier to employment.

BTB policies encourage statistical discrimination on the basis of race: in the pre-BTB period, white applicants received 7% more callbacks than black applicants, but in the post-BTB period, white applicants received 43% more callbacks, showing that after BTB policies were implemented, the racial gap grew more than six-fold.

This gap comes from losses for black applicants without CR and gains for white applicants with CR, despite the fact that BTB is often thought of as a tool for reducing racial disparity in employment.

This suggests that when employers lack information about CR, they tend to assume that all black applicants have CR and all white applicants do not.

Neither GED status or one-year gap in employment significantly affected callback rates, despite being proxies that employers use for CR

Previous research on statistical discrimination also suggests that allowing employers to have more access to CR information via internet databases and background checks is likely to reduce racial gaps in employment. The researchers suggest that one potential innovation to BTB policies could be asking employers to also blind themselves to applicants’ names and other potentially racially-identifying information unrelated to job qualifications, such as home addresses. Another option is to alter employers’ underlying incentives to encourage them to want to hire people with CR, such as tax incentives or reductions in employer liability from negligent hiring lawsuits. One shortcoming of this study is that it does not provide information on actual employment outcomes in the real world, which is addressed by the work of Doleac and Hansen 2016.

Doleac and Hansen 2016: The unintended consequences of BTB: statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when CR are hidden

The researchers estimated the effect of BTB policies on employment for young, low-skilled black and Hispanic men by using the variation in the timing of BTB policies to test BTB’s effects on actual employment outcomes. They used individual-level data from 2004 to 2014 in the Current Population Survey (CPS) for more than 855,000 men. The study considered three groups: white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic, with three levels of education: no high school diploma, no college degree, and finished college degree. The primary focus was on the probability of employment for black and Hispanic men aged 25-34 without college degrees. The various aspects of BTB policies’ effects are summarized below:

BTB reduces employment by 5.1% for young, low-skilled black men and by 2.9% for young, low-skilled Hispanic men. Both effects are unexplained by pre-existing employment trends, and the effects are larger for those with the least education.

Effects of BTB varied with the local labor market:

BTB had a smaller negative effect on black and Hispanic men in places where a larger share of the population is black or Hispanic, which are the South and West, respectively.

Statistical discrimination based on race is less prevalent in tighter labor markets; BTB’s negative effects are larger when national unemployment is higher.

White men: BTB has slightly positive effects when unemployment is low, but the effect is near zero

Black men: effects of BTB is large and negative even at low unemployment, and the negative effect becomes statistically significant when unemployment reaches 7-8%

Hispanic men: effects of BTB gets more negative as unemployment rises, and the negative effect becomes statistically significant when unemployment reaches 7-8%

BTB has persistent effects over time for black men

For white men: Across all years, BTB’s effect on white men is near zero

For black men: BTB reduces employment by 2.7% in first year, 5.1% in second year, 4.1% in third year, and 8.4% in fourth year

For Hispanic men: reduces employment by non-significant percentages, and effect declines to near-zero after 3rd year

This suggests that young Hispanic men adapt to the policy over time, perhaps using labor market networks to find jobs

BTB effect by type of BTB law: those affecting private employers, those affecting private employers with government contracts, and those affecting public employers (only government jobs)

For black and Hispanic men: adding private firms to has no significant additional effect

For white men: adding private firms increases employment by 4.5%, a large and statistically significant effect

Older low-skilled black men, older low-skilled Hispanic women, highly-educated black women, and white men are significantly more likely to be employed after BTB

Supports the hypothesis that the racial discrimination is statistically-based (employers rely on the fact that young, low-skilled black and Hispanic men are more statistically likely to have a CR or be recently incarcerated), not taste-based (discrimination based on the fact that employers simply don’t like people with CR).

Employers may respond to BTB by shifting preference towards applicants who are less likely to have had contact with the justice system

This study complements Agan and Starr 2016 by showing that changes in callback rates in pre- and post-BTB periods do result in the same changes in hiring. The results also add to the body of research that suggests that statistical discrimination by employers increases when information about job applicants is less precise. Thus, the decision-making process where applicants are not judged individually but rather are compared with other applicants in their group can explain the effects of BTB.

Atkinson and Lockwood 2014: Benefits of BTB - A case study of Durham, NC

This is a report from the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, studying the effects of BTB in Durham, NC. The authors found that the share of people with CR hired by the city government increased after BTB was implemented in 2011. But this study was mentioned in the Doleac congressional testimony, where Doleac counters that the study does not account for the fact that unemployment fell dramatically in Durham during the time period of 2011-2014, and that a tighter labor market usually means employers will hire more people with CR, as found in Doleac and Hansen 2016. This unaccounted factor may have confounded the results such that the increase in employment for people with CR may not be directly or entirely attributable to the BTB policies. However, this study is still widely-cited by supporters of BTB.

In addition to detailing reasons why communities need BTB and the history of the BTB movement, the report also cites information on the benefits of BTB and other fair hiring policies, such as increasing the tax base, decreasing crime, and helping employers:

a study in Washington state showed that providing job training and employment to a formerly incarcerated person returned more than $2,600 to taxpayers (FN 12)

Western & Becky Pettit, Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effects on Economic Mobility, THE PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS (2010) available at http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/CollateralCosts1pdf.pdf.

A similar study in Philadelphia found that hiring 100 formerly incarcerated people would increase income tax contributions by $1.9 million, boost sales tax revenue by $770,000, and save $2 million annually by reducing criminal justice costs associated with recidivism. (FN 13)

Economic Benefits of Employing Formerly Incarcerated Individuals in Philadelphia, ECONOMY LEAGUE OF GREATER PHILADELPHIA (2011) available at http://economyleague.org/files/ExOffenders_-_Full_Report_FINAL_revised.pdf.

Employers benefit from fair hiring policies

employees with criminal backgrounds are 1 to 1.5 percent more productive on the job than people without criminal records (FN 16)

Eamon Javers, Inside the Wacky World of Weird Data: What’s Getting Crunched, CNBC (Feb. 12 2014) available at http:// www.cnbc.com/id/101410448

In terms of employment outcomes, the authors found that the overall proportion of people w CR hired by the City of Durham has increased nearly 7 fold since BTB was implemented in 2011. They also found that even after employers conducted CR checks and found some criminal history, 96% of Durham County applicants with CR were still hired.

The authors state that the success in Durham is not isolated, and cites similar results in Minneapolis (FN 27: Michelle Navidad Rodriguez, Ban the Box’ Fact Sheet, NATIONAL EMPLOYMENT LAW PROJECT (2014) http://nelp.3cdn. net/9950facb2d5ea29ece_jsm6i6jn8.pdf)

BTB turns 20

This is a short article published in 2018, 20 years after Hawaii passed the country’s first BTB law, and details some criticisms of BTB:

According to the National Federation of Independent Business, BTB laws unnecessarily mask relevant CR info that affect the safety and security of business, and make the hiring process more difficult

The laws have morphed from a clear reference to a specific CR box on an initial application; the laws have become broader, some including restrictions on employer consideration and use of certain criminal info, adverse action letter requirements, and other requirements involving information far beyond just the box

There is no federal BTB law applicable to private employers, so companies that hire across the country must comply with a hodgepodge of state and local policies, making it difficult for employers

Stacy and Cohen 2017: BTB and Racial Discrimination - a review of the evidence and policy recommendations

This paper synthesizes many other studies done on BTB and racial discrimination, reviewing evidence on job access for people with CR, racial discrimination in the job market and justice system, and the history of BTB. I will be listing studies and other recommendations that I think are relevant but did not have time to read through, in hopes of providing resources to future interns.

Berracasa et al 2016:

found that most employers reported BTB had minimal impact on their hiring processes in DC

Refutes the criticism that BTB creates inconveniences for employers by opening businesses up to litigation, theft, and greater costs of hiring

Found that the number of returning-citizen hires increased both numerically and percentage of all hires, after BTB

BUT factors beyond the BTB law could explain this outcome

Shoag and Veuger 2016:

uses employment in high crime areas to estimate the effect of BTB on ppl w CR, using longitudinal employer household dynamics origin destination employment statistics data, 2002-2013

They found that the census tracts that had BTB had on avg 3.5% higher employment rate

But it’s unclear which demographic groups drive the employment increases

Emsellem and Avery 2016:

Found that CB rate for black men increased after BTB and this shows the law did not reduce employment outcomes for black men, contrary to Agan and Starr 2016

However, Agan and Starr focused on the disparity in CB between blacks and whites

D’Alessio, Stolzenburg, and Flexon 2015: criminal defendants prosecuted in Honolulu for a felony crime were 57% less likely to have a prior criminal conviction after implementation of BTB, showing that BTB reduced recidivism, or at least decreased the likelihood of re-offending.

Rodriguez and Avery 2016: the most effective way to improve employment outcomes for people with CR is to ban the box AND ensure that conviction information is used fairly.

Additionally, this paper states that Agan and Starr 2016 found that BTB laws “effectively eliminate” the effect of having a CR on callback rates, but I don’t remember this being found in Agan and Starr, and I also can’t find the quoted section in the Agan and Starr paper. This claim is worth carefully investigating and confirming since Agan and Starr’s study mainly found negative impacts of BTB.

This paper also outlines some recommendations and alternatives to BTB:

Flake 2019: Do BTB Laws Really Work?

This is a field experiment in which the researchers sent about 2,000 job applications between June and August 2017 to food services jobs, split between Chicago and Dallas. Chicago has BTB laws for private employment, while Dallas does not have any BTB laws. Each application was tracked to see if the employer provided a callback. The goal is to compare callback rates between a BTB jurisdiction and a non-BTB jurisdiction that were similar in racial composition, unemployment rates, and concentration of food-service jobs. A third of the applications in each city used a black-sounding name (DeShawn Washington), another third used a Latino-sounding name (Jose Vasquez), and the final third used a white-sounding name (Connor Meyer). The applicant characteristics all remained constant with respect to sex, job history, educational attainment, and aptitude. The applicants all have a criminal record of felony drug conviction and served 18 months prison time.

The main findings are as follows:

Results refute the contention that BTB laws do not increase employment for ex-offenders

CB rate was 4.4% higher in Chicago and applicants were 27% more likely to receive callback in Chicago, showing that people with CR had an easier time getting CBs in the BTB jurisdiction

However, the author acknowledges that the importance of the 27% figure should not be overstated, because many other differences between Chicago and Dallas could have contributed to the higher likelihood of getting a CB in Chicago

Results also contradict the claim that BTB harms racial minorities

All 3 races had higher CB rates in the BTB jurisdiction, with black applicants experiencing largest increase of 7.1% more CBs

BUT blacks still had much lower CB rates than whites and latinos in both cities, so racial disparities still persist

Latino applicants were 65% more likely than whites to get a CB, while black applicants were 52% less likely than whites to get a CB

Possible explanations of Latino applicants’ strong performance

The cities have big Latino populations so the employers may want bilingual workers

The hiring managers could be Latino, based on the fact that many callbacks from employers were from people with Latino-sounding names or spoke in Spanish for the callback message

Latinos may have benefited from the model minority status in labor intensive jobs based on the stereotype that they are hardworking and motivated

This study is similar to Agan and Starr in that it is a field experiment, whereas most other studies on BTB analyze employment data. This study differs from Agan and Starr because it compares CB rates between BTB and non-BTB jurisdictions simultaneously, while Agan and Starr looked at CB rates in pre-BTB and post-BTB time periods.

A table of the statistics:

Terry-Ann Craigie op-ed for the Brennan Center, 2017

This is an op-ed by Terry-Ann Craigie, whose research finds favorable results for BTB. She argues that despite the negative unintended consequences of BTB, BTB policies should not be repealed as others may argue, because “the more pervasive problem underlying the unintended consequences of BTB is racial discrimination.” This comes from the fact that the negative unintended consequences is due to employers using race as a proxy for CR, which amounts of racial discrimination and is illegal. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s 2012 guidelines clearly state that race should not be used as a proxy for CR. Instead of demonizing BTB policies, Craigie writes, we should hold employers accountable for their discriminatory practices. While Doleac and others believe that BTB laws should be repealed due to their unintended consequences, Craigie wants to keep BTB laws and also implement other policies to address the unintended consequences. Additionally, Craigie points out that her research found that BTB improves employment for those with CR because she focused on public sector employers, while Doleac and Hansen and Agan and Starr looked at public and private employers.

Craigie 2017: BTB, convictions, and public employment (paper in drive folder)

This paper is the first study to focus on the BTB policies on the probabilities of public employment (PPE) for those with CR. The author uses individual-level data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 cohort (NLS97) from 2005-2015.

The major findings are as such:

BTB policies raise PPE by 4 percentage points, and this effect represents about 30% on average of the outcome mean

Results are consistent with Atkinson and Lockwood 2014, Juffras 2016 (in which DC saw 33% increase in employment for those with CR), and Emsellem and Avery 2016 (people with CR accounted for 10% of new public hires in Atlanta)

The study also uses triple-difference (DDD) estimation to test for statistical discrimination against men of color, but finds no supporting evidence

This is contrary to Agan and Starr and Doleac and Hansen, but this study differs from those others by focusing only on the public sector, which constitutes 85% of total employment and where anti-discrimination practices are relatively strong

The results directly contradict Doleac and Hansen, which finds that BTB has negative effects on PPE for young low skilled black men, but that may be because Doleac and Hansen used a race-differential model (which shows outcome differences between BTB and non BTB jurisdictions for young low skill black males) while this paper uses DDD (which shows the net impact of BTB on PPE for blacks relative to whites).

These results (finding no statistical discrimination) are consistent with

Shoag and Veuger 2016

Jackson and Zhao 2017

Rose 2017

These results contradict

Agan and Starr 2016

Doleac and Hansen 2016

Hirashima 2016

This study also finds that BTB policies increase PPE over time.

The author acknowledges 2 main limitations

The sample is relatively small

But power tests and national survey comparisons confirm that the data is good enough

The timing of most BTB policies coincide with the post-Great Recession period, which is a relatively tight labor market

Thus, we need to better understand how public employers respond to BTB over the business cycle, especially during periods of high unemployment

Colorado Center on Law and Policy: BTB effective at boosting employment

This report synthesizes various studies that demonstrate positive impacts of BTB. The studies cited could be additional useful resources for future research.

Final list of papers and other resources to look into:

Jackson, Osborne, and Bo Zhao. 2017. “The effect of changing employers’ access to criminal histories on ex-offenders’ labor market outcomes: Evidence from the 2010-2012 Massachusetts CORI reform.” Federal Reserve of Boston Research Department Working Paper 16-30.

Shoag, Daniel, and Stan Veuger. 2016a. Banning the Box: The Labor Market Consequences of Bans on Criminal Record Screening in Employment Application. Working Paper.

Shoag, Daniel, and Stan Veuger. 2016b. No Woman No Crime: Ban the Box, Employment, and Upskilling. American Enterprise Institute working paper. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Rose, Evan. 2017. “Does banning the box help ex-offenders get jobs? Evaluating the effects of a prominent example.” Working paper, available at https:// ekrose.github.io/ files/ btb seattle ekr.pdf

Berracasa, Colenn, Alexis Estevez, Charlotte Nugent, Kelly Roesing, and Jerry Wei. 2016. “The Impact of ‘Ban the Box’ in the District of Columbia.” Washington, DC: Office of the District of Columbia Auditor

Emsellem, Maurice, and Beth Avery. 2016. “Racial Profiling in Hiring: A Critique of New ‘Ban the Box’ Studies.” Washington, DC: National Employment Law Project.

Rodriguez, Michelle Natividad, and Beth Avery. 2016. “Ban the Box: US Cities, Counties, and States Adopt Fair Hiring Policies.” Washington, DC: National Employment Law Project.

D’Alessio, Stewart J., Lisa Stolzenberg, and Jamie L. Flexon. 2015. “The Effect of Hawaii’s Ban the Box Law on Repeat Offending.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 40 (2): 336–52.

Rodriguez, Michelle Natividad. 2016. “‘Ban the Box’ is a Fair Chance for Workers with Records.” Washington, DC: National Employment Law Project